Expanding Social Justice with Serious Play

Partner

The Equitable Futures Project/Oakland Schools, Oakland County, Michigan

Duration

September 2019 - April 2020

Role

Designer & Principal Design Researcher

Overview

Is imaginary play the critical missing piece for advancing social justice education? This project tested an unconventional method for engaging educators in this critical effort. Serious play, the act of play pursued purposefully to achieve a significant goal, shows promise as a participatory design method that makes the tension between the desire for equity and the fear of losing of power or status explicit to players. Explored through the lens of Equitable Futures, a Michigan-based project aimed at bringing a social justice perspective to classroom instruction, classroom teachers across Metro Detroit and Berkeley, California participated in serious play with the goal of emerging implicit attitudes connected to social justice education while taking pleasure in the process. The project underscored the importance of designing supportive conditions that allow players to vulnerably express their challenges through a novel mode of problem solving and boldly imagine new ideas for increasing access to student learning in safe play-space free of immediate repercussions. The project has implications for those active in equity and social justice work, demonstrating that serious play is a potentially effective way to increase dialogue around difficult topics and co-create new solutions to wicked problems.

Problem

Many Detroit-area teachers expressed outward support for Equitable Futures and it’s approach to social justice education. However, the project’s founders observed a drop in teacher enrollment in the professional learning course associated with the curriculum, suggesting a discrepancy between the level of expressed interest and total enrollment. With an initial objective of designing a strategy to increase teacher enrollment in the Equitable Futures program, the situation presented an opportunity to instead probe into the dilemmas faced by teachers engaged in social justice curricula. This prompted the design team to ask what are the barriers, real or imagined, that stop teachers from meaningfully teaching their students about social justice?

Founded in 2015, the Michigan-based Equitable Futures Project has engaged more than 3,000 students in its six-week high school U.S. History curriculum about Civil Rights. The program leverages project-based learning to engage students in collaborative inquiry into the partisan perspectives written into prevailing U.S. historical narratives. It proactively brings discussions about race, power and politics into classrooms, believing that teaching students how to work together while engaging in dialogue around difficult topics supports the making of a more socially just future.

Partner

Process

A teacher participates in serious play in a workshop hosted in their classroom.

Approach

To generate insights that might address the project’s central question, I developed an integrative design process combining participatory co-design and asset-based design approaches. Participatory co-design intentionally involves stakeholders with direct experience of a design problem as co-equals in the creative process. This approach is shown to produce more sustainable design outcomes. Asset-based design recognizes the efforts already undertaken by communities to address a problem, aiming to improve what already exists. These combined approaches helped build rapid trust between participants and the practitioner, a vital component for encouraging dialogue around challenges in implementing the Equitable Futures curriculum.

Methods

A serious play toolkit co-designed with teachers was the primary investigative method for exploring barriers. The toolkit itself was developed through observation, interviews, card sorting, workshops, and iterative prototyping with participants, see A Play Kit Designed for Serious Conversations.

At first a curious choice, the teachers’ desire to “play out” their challenges to teaching social justice makes sense when taking the affordances of play into account. We bring a different self to play than we do to our work. When we are in “play mode” we are more open, communicative, and creative. We feel less self-conscious and more free to be who we are. In the proxy world of play, we can (re)imagine our world - our relationships, our personal behaviors, our institutions, and more - in way that reflects, yet is separate from the our reality. We can leverage play’s affordances to redefine how we uncover problems and create solutions we can integrate into the “real world.”

Data Synthesis

Data in the form of photos and video recording was synthesized into findings using a variety of sensemaking tools, including memoing, critique, and cognitive mapping.

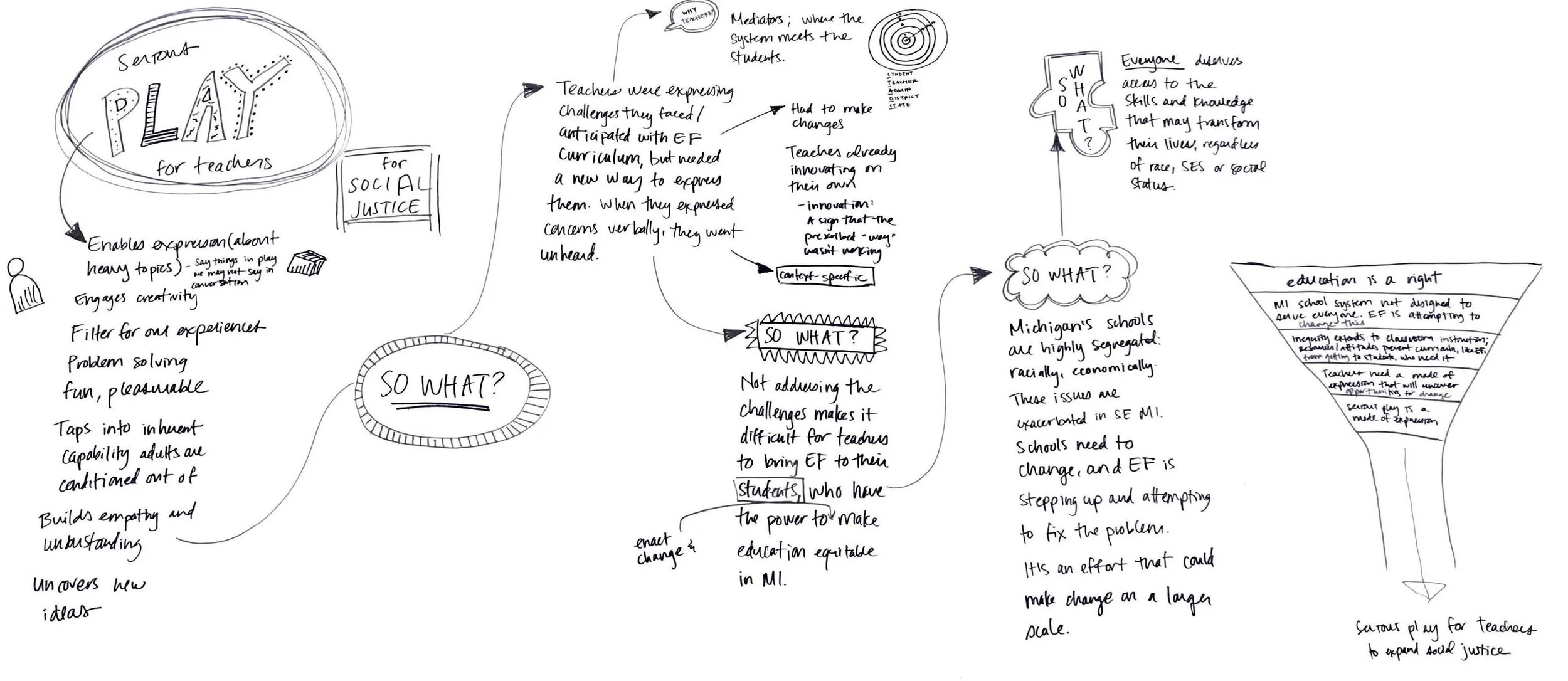

Sample of a cognitive map produced to synthesize data from co-design sessions with teachers using serious play to create access to social justice education.

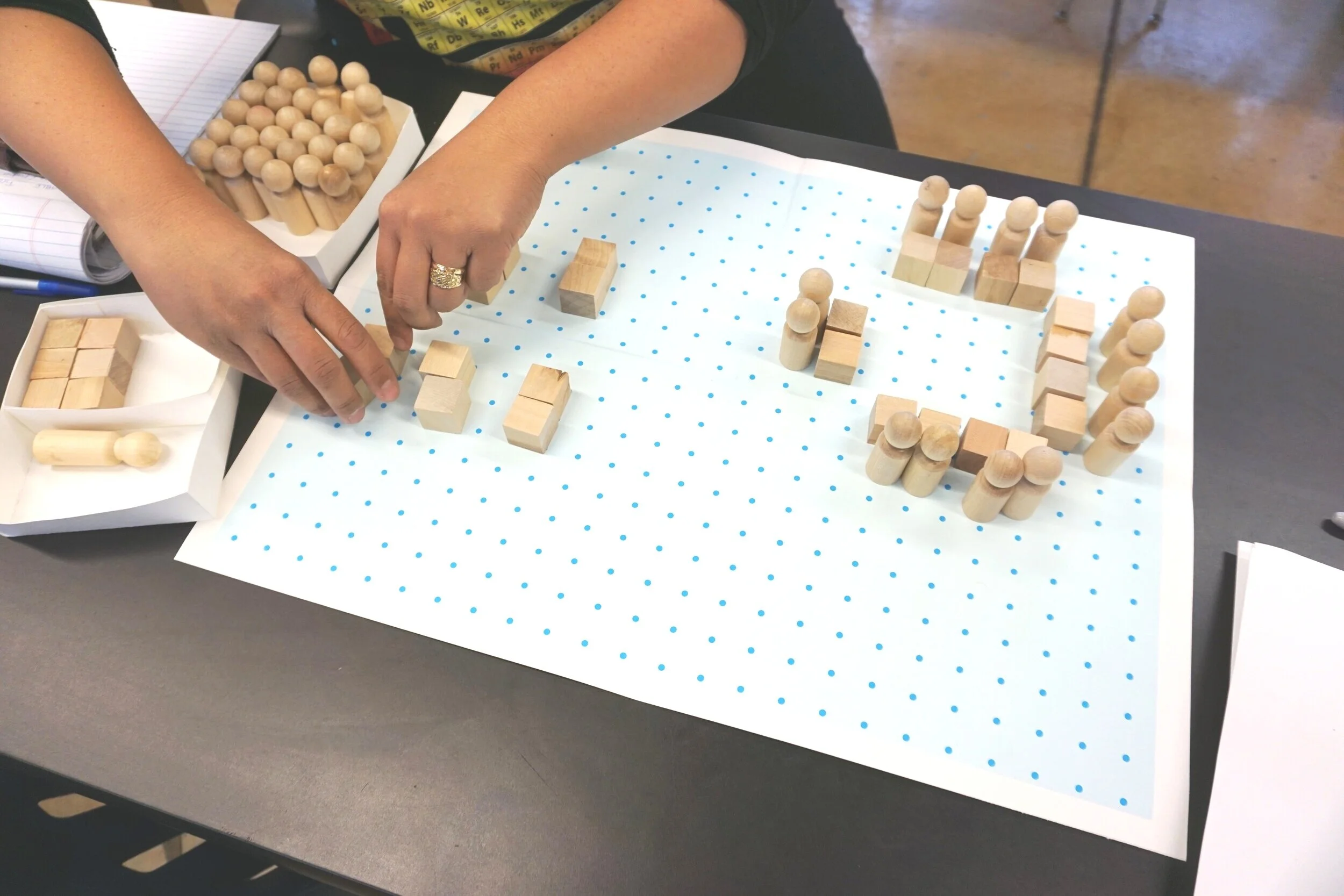

A teacher uses the serious play toolkit to explore alternative classroom configurations for disrupting embedded systems of power in learning spaces.

Findings

Serious Play for Social Justice

Results of the project point to serious play as strongly supporting efforts to increase student access to social justice education in schools. It does this by giving teachers a bounded “play space” to express their barriers - often taking form as fear of backlash, loss of credibility, or loss of power - as well as practice responses to these fears, should they arise, that would not compromise student learning about social justice issues.

In some sessions, serious play led participants to uncomfortable truths about their teaching practice. For example, one teacher used the serious play toolkit to model how they like to center themselves during large group discussions in their classroom. Commanding attention helped to minimize any “Lord of the Flies moments.” When asked if they thought this helped their students dialogue about social justice issues, the teacher looked at the model they assembled and said “I kind of probably take a little bit more control of this than I probably should.”

The practitioner then guided the teacher to use the serious play toolkit to imagine a new reality for their classroom. This time, the teacher created a scenario where the students had more autonomy in the discussion.

This exercise provided this teacher with new ideas for democratizing dialogue around social justice. They later had this to say in a follow-up interview:

“I really liked using the different objects to visualize my classroom and discussing ways in which we could maximize student participation.”

The “light approach” of serious play turned the difficult experiences of raised awareness to one’s behaviors and problem solving into something enjoyable, something to be “liked.”

Framing is Key

Taking part in imaginary play and realizing potentially uncomfortable truths about oneself are vulnerable activities for adults. As a collection of loose parts, the serious play toolkit won’t overcome strong emotions on its own. This process highlights the importance of designing the proper conditions for teachers to take up serious play to explore and transform their barriers connected to social justice education.

Key learnings include:

Create a safe space. Encouraging candid conversation around challenging topics requires sanctioned spaces where participants may speak freely without their self-identity or integrity coming under threat.

Create a brave space. Construct contained “zones” where ideas and emotions may be expressed and processed, drawing respect and understanding between participants. Giving participants permission to break down existing boundaries helped build brave spaces for co-design.

Play with simple, tactile objects. These elements, such as wood blocks and figures, are flexible and invite imagination. Advanced creative tools, like artist markers and clay, diminish participation by implying creative mastery.

Conclusion

Play rarely arises as an approach for confronting injustices, but results of this project suggest it deserves a closer look. Through participation in serious play, teachers recognized how ingrained habits, attitudes and beliefs were unintentionally getting in the way of educating their students about social justice. These were connected to dilemmas they faced around race, gender, class, and political affiliation, among others.

Serious play also enabled teachers to imagine alternative ways of responding to these dilemmas that would align with the visions they had of themselves as teachers.

Ultimately, it is the decisions made when facing dilemmas, moral inflection points, that determine the degree to which social justice is practiced in the classroom. Providing teachers with a tool to build their capacity to consciously make decisions that will further advance access to transformational learning is a first step towards the building of equitable structures, first in schools, then in society. Will the serious play toolkit resolve all of society’s inequities? Most likely no. However, the unlikely pairing of play and the consequential work of progressing social justice is one that anyone interested in social justice efforts is encouraged to continue to iterate upon.